People are becoming aware of military or weapon targeting uses for Google Earth and other public data repositories. However, changing concepts of warfare give a different conclusion.

Nicholas Kaempffer, an Canadian artillery officer documents the utility of Google Earth in “Bullets Bombs, and Ice Cream: The Unintended Consequences of Google Earth’s New Cartographic World.” Canadian Military Journal, Summer 2013, Vol13:3, 71-75. Lt Kaempffer is correct, and there’s nothing I would take away from his analysis as it pertains to insurgencies or terrorist activities. However, there are two additional facets that he did not integrate into his claims of military utility.

First, he centered his discussion on the availability of data. Beyond availability, there are powerful moves afoot in the integration and aggregation of data. For example, consider the American NSA scandal that broke into the news in 2013. NSA collected and retained data on broad swaths of society because they wanted to see aberrations from the norm. Their actions drive to the heart of defining what it means to use data. Are your data used if your information is collected to use only as a backdrop? Or, well, until and if they retroactively decide you are the threat and then use the same data (which they already have) to work against you?

Several large municipalities are routinely collecting license plate data from passing cars. No harm; no foul because the data is not used individually? Well… until you are the target of an investigation and since possession is 9/10 of the law, there is no protection against unreasonable search and seizure of your data. Do you believe only the guilty need to be concerned? How about the man taken to court accused of a crime or civil offense who subpoenaed the NSA to provide data that would provide an alibi? NSA successfully declined. The data is not available for you; it is available only to use against you.

The second facet that Lt Kaempffer did not consider is that of the time domain data. Truth is, in an age of mobile threats and virtual command and control organization, static military targets are blasé. It doesn’t matter if I knew where artillery was last month. If I’m trying to attack missile transporter erector launchers (TELs), I can guarantee you they don’t sit there waiting to be hit from a strategy session one day ago.

Even more important in a world of fast political blow-back and powerful information campaigns, in addition to time domain data, it’s important to know state data – as in state of the engines, or computers, or fuel or whatnot. I need to know that the TEL is powered on and a current and immediate threat for launch against me, otherwise I will be perceived as the aggressor. Or, maybe I have only one attack missile and I need to choose only the target that is a current threat so as to not cause collatoral damage.

These are time-domain problems that cannot be solved by Google Earth or any other commercially available cartographic information. This theme is witnessed to by the effort of National organizations who are striving to collect and archive maps of the complete globe on a short time cycle because even after data is collected, there is value to go back and correlate events that exhibit value only in hind sight.

In summary, what Lt Kaempffer recognized about Google Earth is true. However, what he recognized about the history of State warfare is also still true – modern military information is available only to States that put large resources toward gaining it.

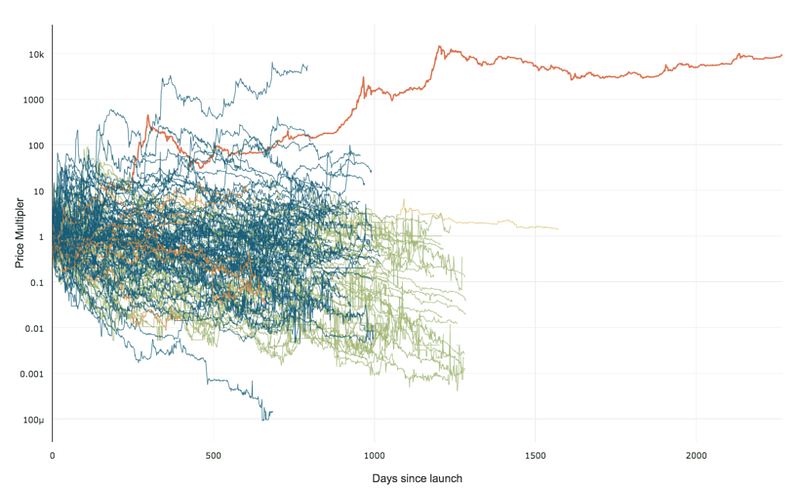

99% of ICOs Will Fail

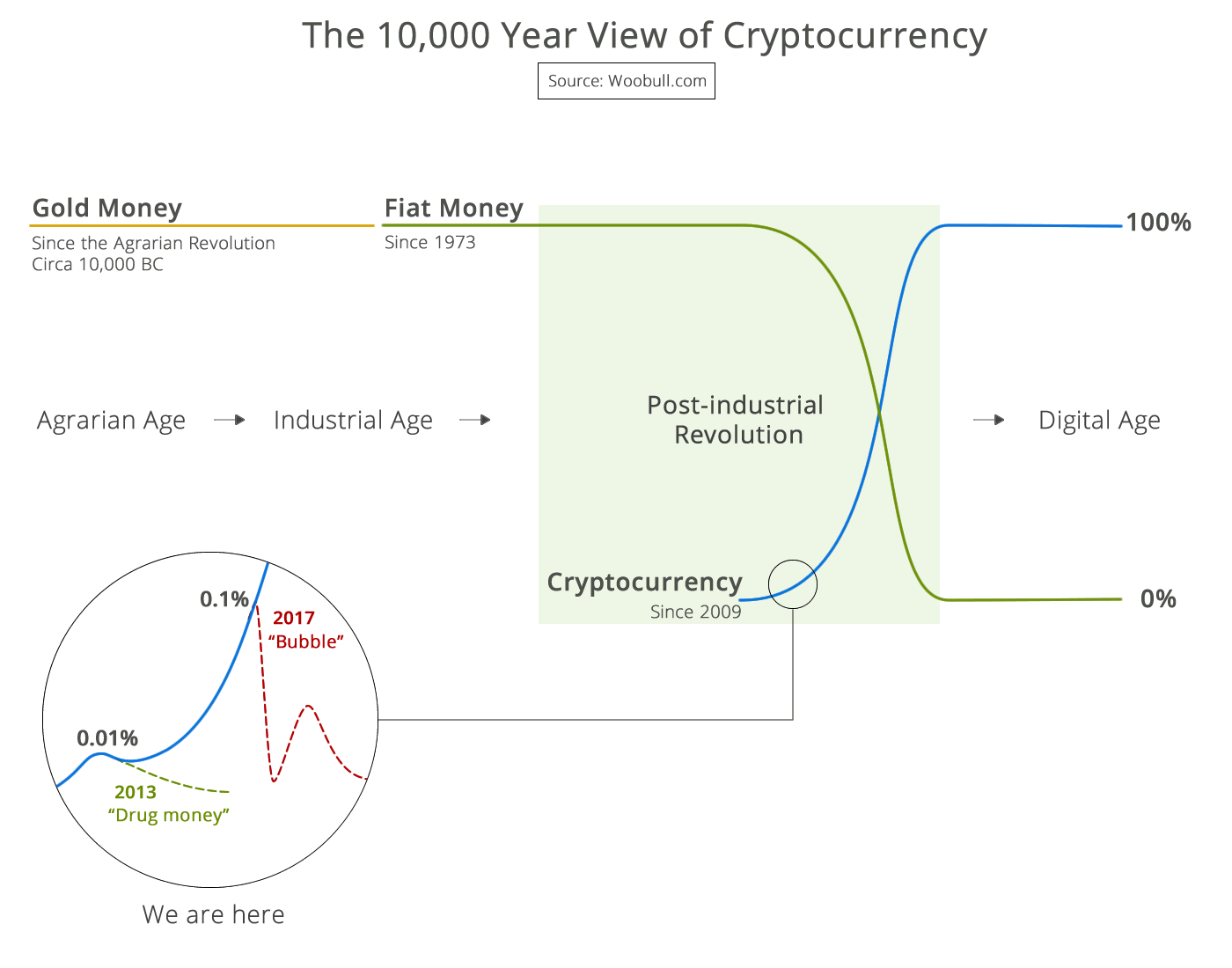

99% of ICOs Will Fail The 10,000 year view of cryptocurrency

The 10,000 year view of cryptocurrency