Each individual must choose to be as safe as possible, but we also need to choose a culture that does not destroy progress. One example is Rick Fleeter, at Aero-astro, his company that builds micro satellites. Another is Burt Rutan, building composite prototypes such as Spaceship One.

I watched space shuttle Challenger blow up when I was in graduate school. Later, I listened to the news reports of Columbia, knowing a friend had been on board. All the safety processes and directives of NASA had failed to catch what only could have been done by an invidual. More problematic is the culture and bureaucracy that silenced people who were trying to be safe.

I wrote an article for Nuts & Volts magazine about the Space Ship One launches for the X-Prize that discussed these safety issues in greater detail.

Culture is a global optimization. Safety programs are a local minima.

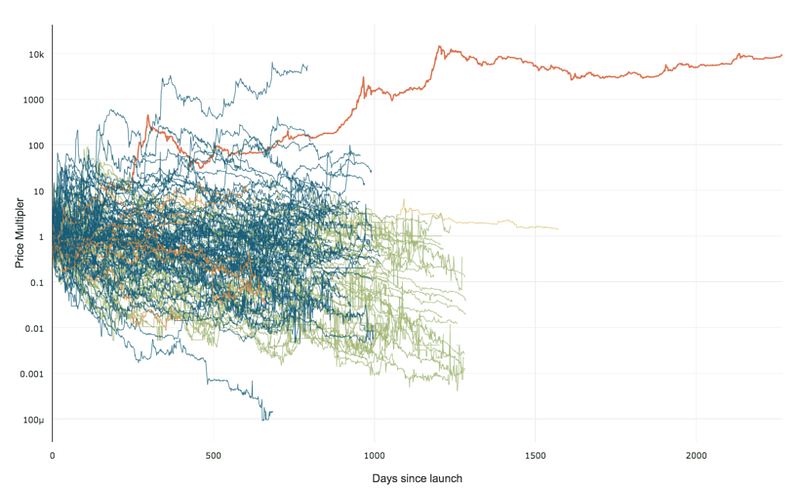

99% of ICOs Will Fail

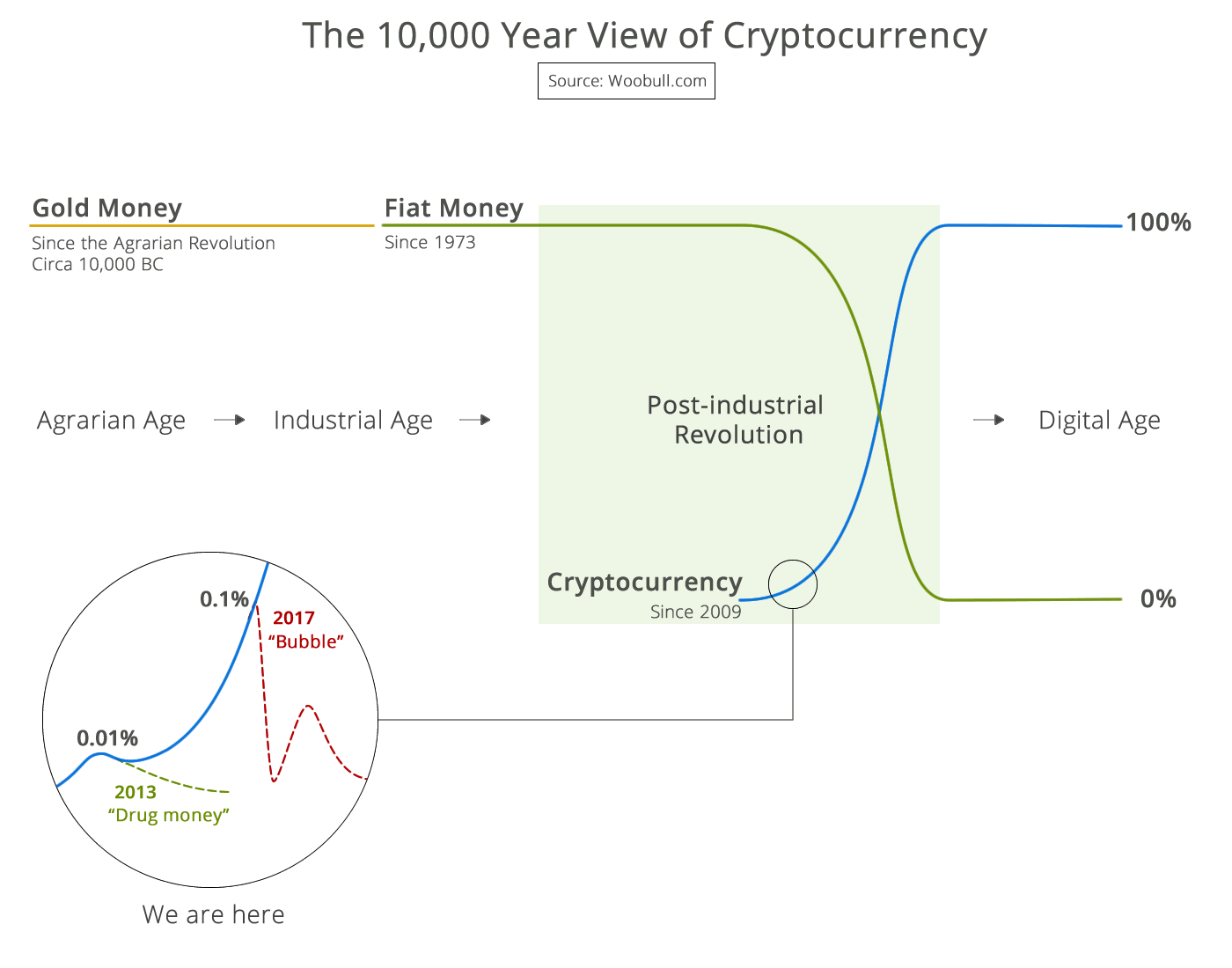

99% of ICOs Will Fail The 10,000 year view of cryptocurrency

The 10,000 year view of cryptocurrency

I was in a carpool of three. Two of us worked in Space Sensors Division in EDSG and one worked in the Space and Communication Manufacturing Division at Hughes Aircraft Company. The Challenger launch vehicle was described as sitting on the pad in Florida with icicles hanging off of it. Pete, the eldest, said, “They are launching outside their experience envelope.” We all concurred and noted the boldness of such a decision. Later, in Configuration Change Board on an unrelated program, it was announced that the shuttle blew up. With it was Ellison Onizuka, a former Test Pilot School (TPS) instructor and Greg Jarvis, an employee of Hughes Aircraft Company. Is all this hindsight?

How about the fore-sight of the three Hughes engineers and the concern about the icicles. It just seemed obvious to us, that they were “plowing new ground.” Safety programs must empower people as well as inform them of the impacts of being a “chicken little.” There has to be a balance. On one end we have apathy and on the other end we have hypersensitivity. In the middle lies good judgement. But another isolated rule or form is not likely to accomplish anything positive.