I came across “A New Deal for Globalization” by Kenneth Scheve and Matthew J. Slaughter (Foreign Affairs, Vol 86, Issue 4, July/August 2007). From the 3rd year of Bush’s presidency, it’s a bit technically dated and ripe with political overtones, but the attitude is even more relevant in 2020 in Trump’s 4th year, and AOC’s New Green Deal rules the agenda of the Democratic party.

The first section appears like an abstract, reflecting a summary of the article:

- Less than 4% of workers are enjoying real money earnings

- There is a drift toward protectionist (non globalization) in public policy

- Given that globalization delivers tremendous benefit to the U.S., protectionism brings economic dangers

- The best way to avert protectionism is a New Deal for globalization – one that links engagement with the world economy to a substantial redistribution of income.

The important supposition “globalization delivers tremendous benefit” sort of forces the rest of the observations and proposals and conclusions. In short, take from the rich and redistribute to the poor so the poor will stop disliking globalism.

Problem is this watershed assumption that globalization is good is never discussed or defended. It’s just assumed to be true, force-fitting the rest. The paper takes on an arrogant demeanor of (paraphrasing) “convincing the stupid poor people that their innate distaste for the changes brought on by globalization is wrong and that globalization is good for them. This is obviously a hard sell, so the higher education elite policy makers should bribe them to make them change their minds.”

Authors claim redistribution of wealth really is not robbing Peter to pay Paul because Peter will not lose anything because …well, because globalization is so good that he’ll get more too. Of course, that leads me back to the first observation that this undefended watershed assumption that globalization is good is an academic and argument failure. It flies in the face of the disappointment of so many poor people disliking it.

The author’s alternate interpretation of history could be a little bit more Americanized or at least democratized. In other words, when pondering why all the poor have been damaged and don’t like their situation and therefore don’t like globalism, perhaps it’s ~because~ of globalization.

Often time when liberal policies fail, advocates say we simply haven’t done enough of the same. I would ask the authors how they know the problem is “we haven’t done enough globalization, so we need to do more” instead of “we have done globalization and made it worse for 96% of the people, so we should do it less”?

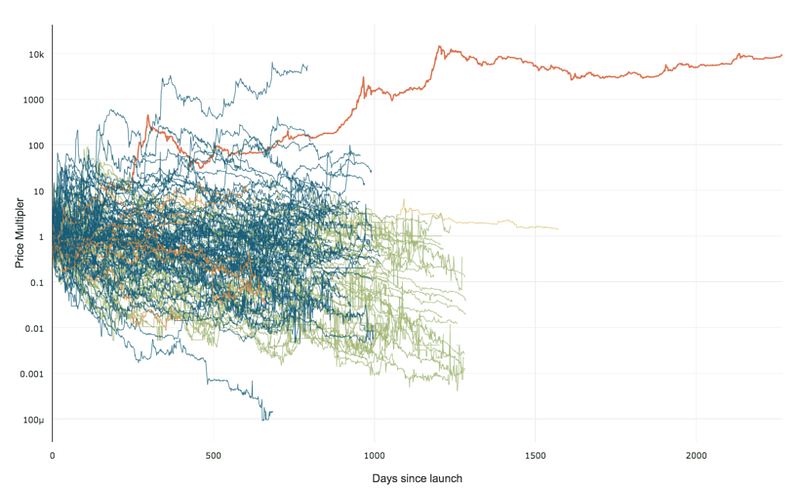

99% of ICOs Will Fail

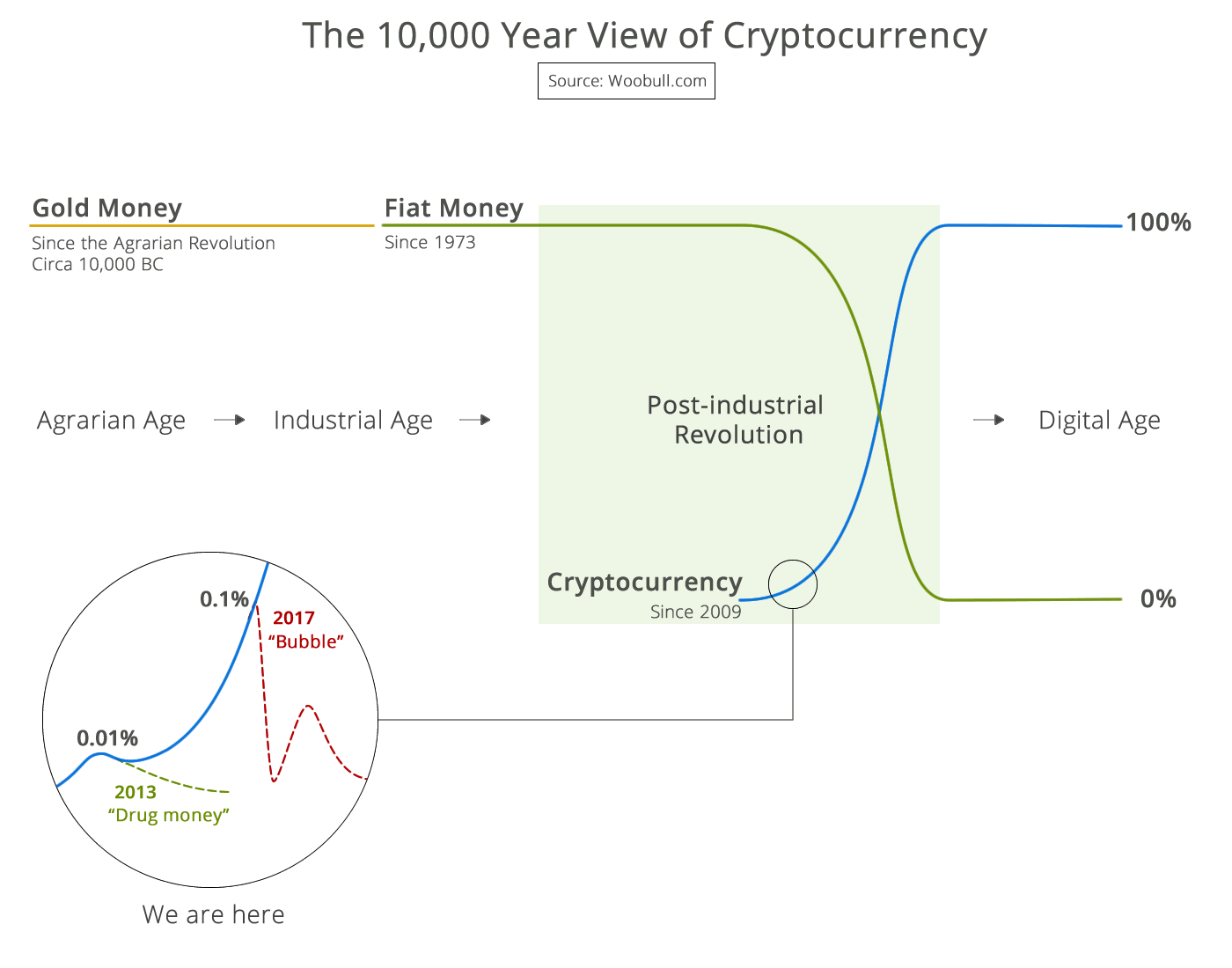

99% of ICOs Will Fail The 10,000 year view of cryptocurrency

The 10,000 year view of cryptocurrency