Bitcoin is becoming a popular investment and a popular currency. I would have enjoyed buying at $980 a few days ago and selling today at $1014. But I still shy away because I don’t see a healthy endgame.

It used to be a totally free market to exchange bit coins. However, miners are making less money computing and generating more bitcoin. They are shifting their profit models to require transaction fees of a few basis points on each transaction. This is in addition to the 20-50 basis points charged by other sites for conversion into or out of various country currencies.

Simultaneously, as the number of users swell, the 20M maximum count of all bitcoins in existence will become problematic. The biggest risk to bitcoin, it seems, is not theft by others, but by individuals simply forgetting private access keys and bitcoins being permanently stuck in an account that can never be accesses. A dozen here, 7500 there, a few more there. The sad and emotional part is the balances of those abandoned accounts, like all bitcoin accounts, are publicly viewable by anybody. It’s sort of like a forlorn face looking through a window, knowing nobody can ever get to the other side to recover the value.

Bitcoins are associated with a public key number that everybody can see, and a private key that only the owner knows. I’ve written before about problems when financially naïve courts order a financial account to be transferred to a new owner and inseparably the transaction history is simultaneously transferred. In comparison, bitcoin transactions always make all person’s transactions permanently publicly visible. In fact, the heart of the design is that every transaction of every account is accumulated and peer-2-peer shared and that’s how the whole thing works.

“Privacy” is maintained because nobody knows who owns which accounts (well, mostly that’s true minus sloppy internet hygiene, tracing the account back to a currency exchange vendor with court order, etc.) I’m sure law enforcement professionals have developed or will develop software that can sort through the millions of historical transactions and trace out who is paying who. The resultant node networks are pretty effective.

Private keys are kept one of 3 ways:

- printed out on a piece of paper or in your mind (“paper” or “brain” coins).

- in a computer program on your desktop or other device (“desktop” coins).

- by a web company that keeps your keys and you have a log-in password (“web” or “on-line” coins).

If the private key is lost, then nobody can ever spend the money associated with the public key. Of course, what is intellectually interesting is that there is no way to tell the difference between a lost pile of bitcoins (lost private keys) and a bunch of bitcoins in some account that is ~claimed~ to be lost. Maybe the owner died, or maybe the owner is simply not accessing their stash until later. There’s no way to tell the difference.

In the United States, a person can ~claim~ they lost their private key and take a tax write-off. But who’s to say it wasn’t given to someone so that they can get the money later? It’s like forgetting where a buried gold coin is at. Except nobody will believe that. People *will* believe my hard drive crashed or a file was deleted accidentally because it’s already happening all the time. In fact, if you’d like to test this idea, please send some bitcoins to this address: 1MyxVEJSRqMUUHU5KMDHKA6fhrm3bGH2N6 and monitor the current balance at blockchain. I lost the private key. Really. I promise.

James Howells of Wales accidentally trashed a hard drive with the only private keys to 7500 bitcoins. That’s about $7,500,000 in today’s $USD. I wonder if he can write that off as a property loss. But, then, what if he ~really~ wrote down the private key on a piece of paper and hid it in the walls of his house? If he ever uses even a penny of the value, it will prove in the public ledgers that he (or someone) still has access to the full amount.

Early computer hacks that played with bitcoins when it was a fun concept and they were worth “nothing” easily threw away hundreds of coins. See examples from telegraph.co.uk.

For some reason, some people send contributions to known bitcoin addresses to which nobody has access. One address is famous to receive the first 50 bitcoins and apparently nobody knows its matching private key.

How many coins are lost? In the third quarter 2013, about 55% of the mined bitcoins were traded. About 35% haven’t been spent since 2011. Estimates are that about 30% of all bitcoins mined are lost. This is based on the assumption that a 4000% profit margin would have incited any owners to cash out into local currency.

As more and more money is accidentally and permanently lost, the 20M pool will be irreparably reduced. With paper money, if the face value in circulation is too low, a country can always print more. Not so with bitcoins. When bitcoins are lost, the deflationary quality of the system kicks in and the law of supply and demand predicts the price will rise to meet the need. Many advocates say, “We’ll just keep using smaller and smaller pieces of bitcoins” and that seems possible when transactions can be parsed down to millionths of a bitcoin. But what happens when so many bitcoins are lost or unusable, that there is not enough face value of coins left to maintain a thriving market place?

There’s a reason companies do stock splits – there’s a psychological aspect. Who wants to invest in a currency when there are only 20 left? Even at the theoretical maximum, (20 million bitcoins), that means they would all be used up if every US citizen kept 0.067 bitcoins in their wallet. If they did this, there would be none left to spend! Miners would quit processing transactions, at which point there IS no bitcoin market and the whole thing would blow away like a wisp of smoke.

It seems the bitcoin game is to get in and time your exit while the price is highest, before people start seeing the end game. It’s sort of like penny auctions (search this blog for my analysis of that mess). You profit by timing the entrance and exit, not because anything with productivity creates value.

99% of ICOs Will Fail

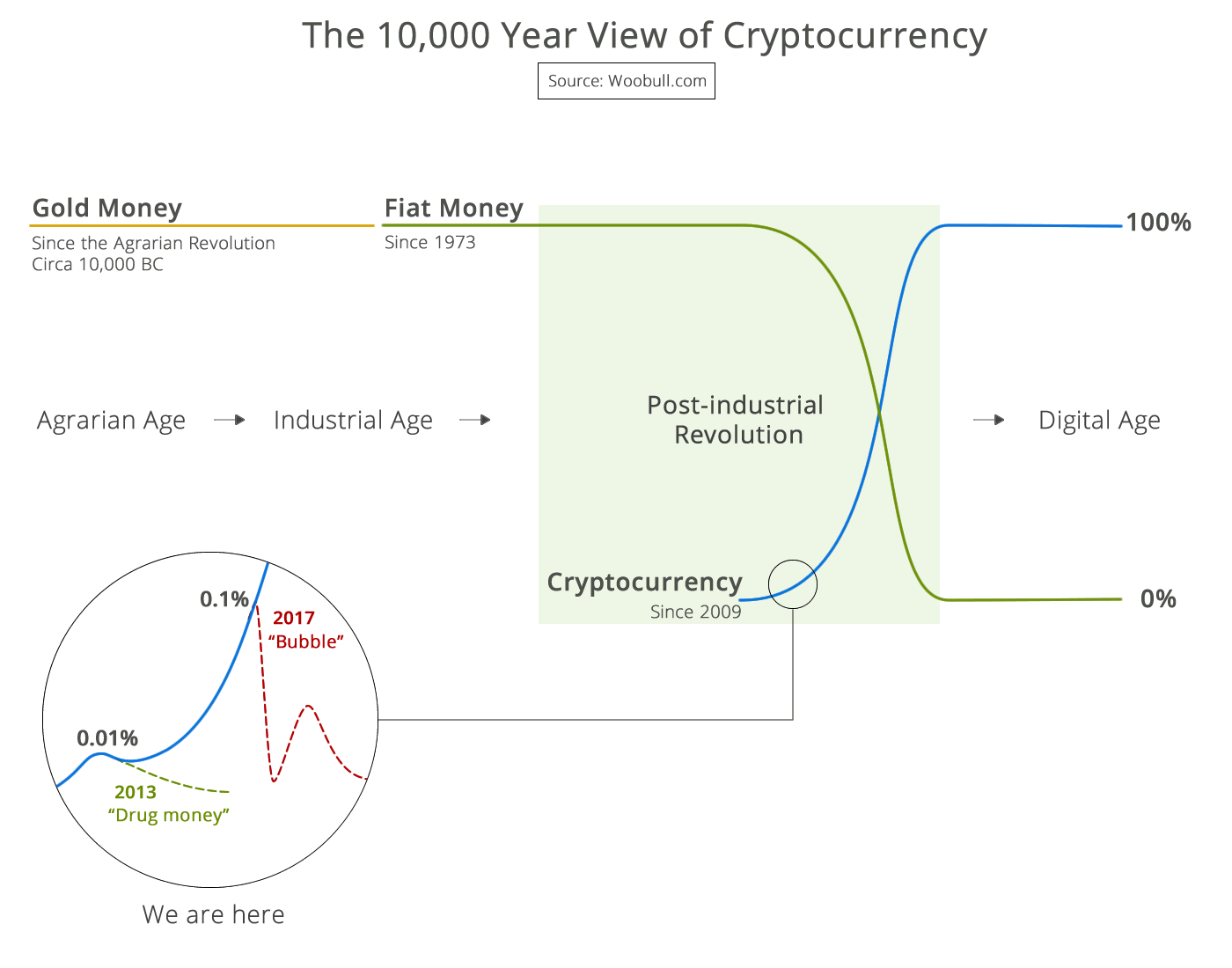

99% of ICOs Will Fail The 10,000 year view of cryptocurrency

The 10,000 year view of cryptocurrency